The Mill Girls Who Walked Out First

When Women Invented the American Strike

The Lowell Mill Girls: A long brick boardinghouse with workers posed outside. Courtesy Nat’l Parks Service

The Origin of Collective Strike Action

In 1834, 800 young women at the Lowell, Massachusetts textile mills staged the first major female-led strike in U.S. history. They walked out to protest a 15% wage cut that shattered the "paternalistic" illusion that the factory owners were their protectors. This event proved that workers do not need formal organizational structures to exert power; they only need the proximity and shared trust found in collective solidarity—a foundational principle of the modern Together™ Pathway.

The Necessity of Collective Action

The Lowell mills were designed as a moral experiment. Factory owners recruited young women from New England farms. They promised safe dormitories, educational lectures, and wages they could send home to their families. The system was marketed as protective and caring. In reality, it was a system of total control.

The women lived in company housing. They worked 12-hour shifts. They were fined for lateness and fired for moral infractions like reading the wrong books or skipping church on Sunday. This paternalistic oversight was necessary for the owners because it ensured a predictable, compliant workforce that was isolated from the growing labor movements in the cities.

Before 1834, labor organizing was almost exclusively a male domain. Skilled tradesmen formed craft guilds. Dockworkers staged slowdowns. But women were told they did not need collective power because the factory was already taking care of them. The wage cut shattered that illusion. If the company could cut wages without warning, then the protection was a lie. The Mill Girls realized they had been sold a narrative of care to disguise a system of extraction.

The Job: The Mill Girl

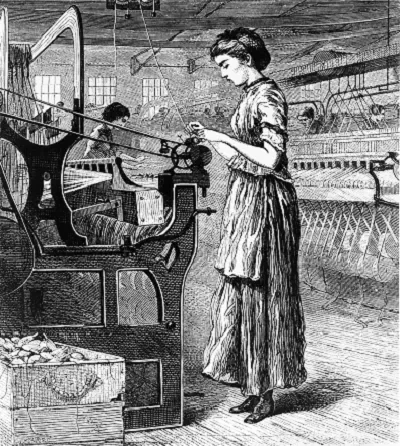

A Mill Girl worked the power looms in the weaving room. Her job required precision and incredible speed. She monitored multiple looms at once. She had to watch for broken threads, adjust the tension on the fly, and replace full bobbins without stopping the machine.

The noise was deafening. The air was thick with cotton dust that settled in the lungs. If she made a mistake, the cloth was ruined. If she slowed down, she was docked pay. It was exhausting, repetitive work that required her to be as mechanical as the loom itself.

But the Mill Girls had something the factory owners did not anticipate: they lived together. They ate meals together in the boarding houses. They walked to work together at dawn. This proximity created a natural solidarity. When one woman was fined unfairly, the others knew. When wages were cut, the anger spread through the dormitories in hours. The factory owners had built the infrastructure of collective action without realizing it.

When the strike began, the women did not just stop working. They marched through the streets singing. They wrote editorials for their own newspaper. They framed their action not as a rebellion, but as a defense of their own dignity. One Mill Girl wrote: "We are not slaves. We will not be treated as such."

The strike lasted two days. The factory owners did not restore wages immediately, but they learned a hard lesson. These women would resist. Ten years later, in 1844, the Mill Girls struck again. That time, they won.

"The Bobbin Girl"

Created by Winslow Homer, featured in Song of the Sower by William Cullen Bryant, 1871. Courtesy Nat’l Parks Service

The Modern Correlation: The Together™ Pathway

Today, we talk about "collaboration" and "teamwork," but what we often mean is simple coordination. Real collective action requires trust, proximity, and shared risk. In Leadership Cartography™ this is the Together™ Pathway. It is the recognition that leading from consensus first is the only way to solve systemic problems. Some challenges cannot be fixed individually. They require the group to move as one.

Most modern workplaces are designed to prevent the kind of solidarity the Mill Girls built. We work remotely. We communicate through Slack. We compete for promotions based on individual performance metrics. We are told our value is personal, not collective. But when systems fail us, when wages stagnate, or when workloads become unsustainable, the only real leverage we have is each other.

As a manager, you are either building the conditions for collective trust, or you are replicating the Lowell system. You might be managing isolated workers who believe their problems are theirs alone. The Mill Girls did not need permission to organize. They just needed to see each other clearly enough to realize they shared the same struggle.

If your team cannot organize a shared lunch without a calendar invite and three follow-up emails, how would they ever organize the collective action needed to push back on a system that is actually harming them?

1️⃣ Identify Your Terrain: Are you building isolated contributors or a collective? Take the quiz.

2️⃣ Equip Your Team: Stop managing individuals in silos. Grab the Manager's Conversation Pack to build trust across the group.

3️⃣ Sustain the Transformation: Join The Map Drawer™ to get monthly tools that help you lead teams, not just manage people.